Tre Johnson:

Yes.

You know, I hear some of those same critiques. I think, for some folks, the idea of seeing even fictionalized black violence on the screen is unfortunate, because I think a lot of people feel like we have already become very viral in seeing the image of black bodies, either through police footage, or, again, captured on cell phones, looped through our social media feeds and across text message chains all the time.

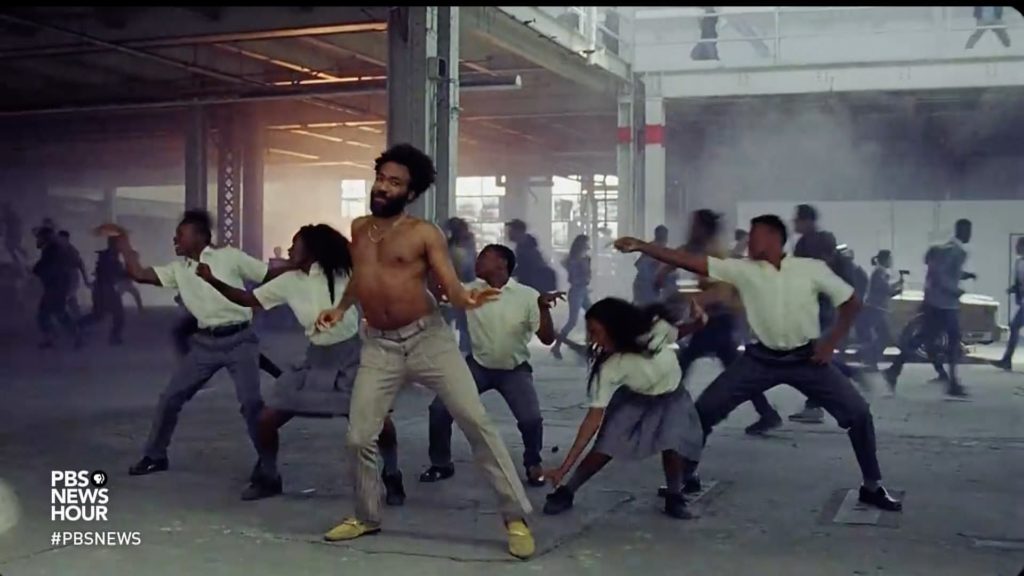

I think, too, again, you know, I think what is jarring about the video itself is that you watch Glover's own kind of facial contortions as he moves from scene to scene to scene. I think there's a desire to see him kind of linger in the despair and acknowledge the deep pain that some of these images are causing for people, or how they are resonant of things that are happening that people identify with all the time, in terms of losing family members or friends or other relatives to gun violence itself.

And then I think, lastly, but what I really challenge people on is, you know, art is going to make people uncomfortable at times. And I think what I really like to do is focus on crediting how much it is that black artists are kind of choosing to take on the hard labor of holding the tension between entertainment and a responsibility to uplifting just more nuanced conversations about American life that I think is often given a pass to some of their mainstream white peer artists.

And so, for me, I'm more interested in the conversation of, what is this art telling us vs. what are the motivations behind it, because I think the conversation that we're trying to have around what this art is producing in front of us is much more worthwhile than trying to scrutinize and parse what everyone's individual motivations are.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejnby4e9OhnGarpJa%2FrHnCoZiorJmYerG71p6pZqeWYrGwusClm2afnKTDpr7SZquhoaNitrR5wKacq6GTlg%3D%3D